The role of an avatar – the protagonist as controlled by the player – is to complete two tasks.

1. Act as a distinct character who relates to other characters as the story dictates.

2. Act as a conduit for the player to affect change in the world.

Avatars might lean more heavily one way or the other. Cole Phelps is slightly more effective as character in a story than as a vehicle for the player because the player usually has no goddamn clue what’s going through his head (Thanks, McNamara). On the other end, we have someone like Doomguy, who is just supposed to be a digitized version of the player, with a gun.

The most effective and memorable protagonists tend to either blend these two tasks into one or veer suddenly from one end of the spectrum to the other at a pivotal point.

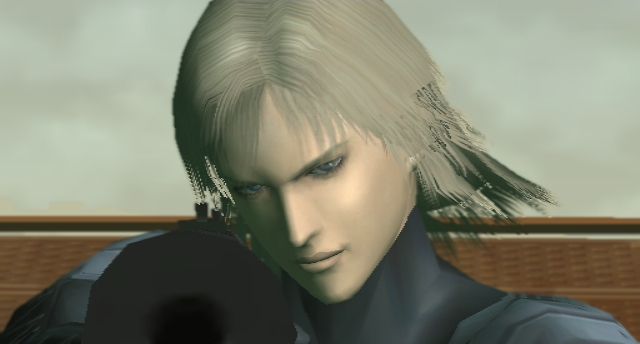

Raiden, in Metal Gear Solid 2, replaces the storied and liked Solid Snake as the protagonist. This position makes him an embodiment for the message of the game – the growing ease of information control and manipulation in the 21st century. And by suddenly and mysteriously replacing him, he also elevates Solid Snake to the status of a legend, something to struggle toward.

Raiden is also an interesting exercise in the development of an avatar. At the game’s start, he’s more like Doomguy than Snake. His personality is pretty vacuous. He has no backstory. According to Rose, even the walls of his bedroom are bare. His girlfriend frets about him, he doesn’t know how to act cool, his only experience with infiltration is in Virtual Reality simulations – video games, basically. If he’s like ANYONE, he’s like the player.

His standing changes toward the end of the game, once the shit hits the fan. Only after he’s discovered Snake’s identity, after he’s been tortured and interrogated as Snake has, and after Snake LITERALLY passes the sword onto him do we discover more about Raiden, his past, and his connection to the antagonist – a child soldier raised by the bad guy who repressed his violent memories, becoming the plain and hollow shell you meet at the start of the game. Only at this point is Raiden trusted to take part in the melodrama and carry the story through to the end. He transitions from empty vehicle to living legend.

Travis Touchdown, of No More Heroes, comes from a similar situation as Raiden’s, but to the nth degree. Whereas Raiden is modeled like a blank slate for the player to project onto, Travis is actually designed as a caricature of the game’s key demographic – a childish, stylized hipster with violent fantasies who likes Quentin Tarentino as much as he likes gay moe anime bullshit. (He also embodies creator Suda51’s own sensibilities as a Japanese developer marketing largely toward Western males – Suda NEEDS guys like Travis to exist.)

He considers himself worldly, but actually has a very narrow set of interests. Despite the size of his hometown of Santa Destroy, the player can only enter places Travis would ever deign to visit: a niche resale boutique, a video store that sells foreign bootlegs, the workshop of the hot doctor where he soups up his lightsaber, and the pro-wrestler’s office where Travis may or may not realize he is not being taught special techniques so much as being molested.

Outside of his fantasy career as an assassin, the rest of the game is framed by his mostly boring life. He makes walking-around money through terrible part-time jobs, eats pizza to heal, and takes a dump to save his data.

But, again, as with Raiden, things change toward the end of the game. Travis discovers that he has complicated, messy relationships with several of the people involved in his line of work, and he’s not very happy about it. Killing people is cool, but matters of family and intimacy is lame and frustrating. While Raiden is liberated by his connection to the story, Travis is trapped by his. His story suggests that, like the player, he wants the fun of the assassin’s lifestyle without any of the drawbacks.

Before I get to Bayonetta, let me talk about one more avatar. This time, from a movie. No, not Avatar!

Tony Jaa in Tom Yung Goong (aka The Protector).

Like all the greatest works of art, The Protector revels in the conventions of its medium while musing on their necessity. At least, I think so.

In the movie, Tony Jaa lives happily in a village outside of Chiang Mai with his elephants, having been descended from a long line of guys who take care of elephants in villages. During a festival, his two elephants – his BEST FRIENDS – are stolen. Apparently, the theft of the elephants are a demonstration of force by gangster Madame Rose, who is simultaneously picking off her competitors so she can run the gang. The elephant rustling is simply the smaller part of a larger plan.

Now, there are scenes of gangsters talking about gangster politics, there’s a detective trying to figure out what they’re up to, politicians who are trying to cover it up – all this PLOT stuff.

Half of these scenes end with Tony Jaa crashing through a window into some dude’s sternum and shouting, “Where are my elephants?!

Tony is in the same corner as the audience. They didn’t come here to watch convoluted and nonsensical political machinations play out. They came here to see Tony Jaa get really super mad at these guys about his elephants.

There’s an argument to the made for the amnesiac protagonist. From the get-go, it puts the character and the player on the same page.

Bayonetta is casually interested in finding out more about herself, but she lives mostly in the now. She knows she’s a witch with supernatural powers, so she’s contractually obligated by demons in Inferno to rebel against the equally monstrous angels of Paradiso.

This works out nicely for her, because she loves beating up angels. And as the star of the single deepest and responsive spectacle fighter of the decade, so does the player.

Boss characters are trotted out periodically who pontificate aloud about their purpose, their plans for the resurrection of their god, and how Bayonetta might be at least tangentially involved. But Bayonetta is too impatient. She routinely tells other characters to shut up unless they are 1) willing to fight, or 2) going to give her something with which to have a more exciting fight with something else.

Before I move on, I think it’s important to point out that Bayonetta’s distinctiveness is most apparent in the playing of the game. Both she and Kratos wreak terrible havoc upon their victims, but while Kratos’s gouging violence is accompanied by blaring horns and Ben Hurr-ish booming percussion, Bayonetta is usually supported by frolicking electro-bubblegum pop as she blows kisses at enemies to lock on to them. It’s like dancing at a club – the catharsis comes less in the violent pay-off and more in the doing, the improvising.

I find that both because of her programming and her attitude, Bayonetta is an effective conduit for the player – you always want what she wants.

That’s why I find it weird that we’re having these issues.

You’ll ‘want to protect’ the new, less curvy Lara Croft

This is an older one, but it was considered pretty problematic when it came to light. Basically, the executive producer of the new Tomb Raider believed that getting players to identify with a female protagonist was a lost cause, so he assumed that players would feel more comfortable considering themselves as Lara Croft’s “helper” or guardian.

I still haven’t played Tomb Raider, so this might just be an executive thinking the worst of his demographic and saying what he assumes they want to hear. But it’s strange in light of this more recent piece of news.

Publishers rejected Remember Me because of female lead

“We had people tell us, ‘You can’t make a dude like the player kiss another dude in the game, that’s going to feel awkward.'” For Morris, that response is puzzling. “I’m like, ‘If you think like that, there’s no way the medium’s going to mature,'” he said. “There’s a level of immersion that you need to be at, but it’s not like your sexual orientation is being questioned by playing a game. I don’t know, that’s extremely weird to me.”

Part of me thought that maybe the story was a PR stunt, or maybe a bit of sour grapes from being rejected by other publishers. But I dunno. Do executives think that female protagonists aren’t worth backing, or is the common player REALLY that uncomfortable stepping into a lady’s shoes?

Only 18% of players were FemShep in Mass effect 3, so, I dunno, I guess so.

It seems like developers believe there are two courses when it comes to making a female protagonist for a video game.

1) Design a decent character, alienate your male audience, and lose money.

2) Design a sexualized character in order to appeal to males, limit publicity out of embarrassment, lose money.

What’s interesting about #2 is that it doesn’t seem to be an issue in the Japanese market. For various reasons.

That’s how we end up with characters like Bayonetta.